_English_

User Tools

Site Tools

Sidebar

4.4 The Journey from Poland to Bessarabia in 1814

Excerpt from the Krasna municipal report of 1848:

„Following this call (call of the Tsar of 1813) the mentioned settlers - 133 families in poor and oppressive circumstances, but looking forward to a better future, left their Polish settlements Orschokowin/Orzechowo and Schitanitz in 1814 under the leadership of Mattheis Müller and Peter Becker….“

However, it is probably the case that emigrants from many other places were involved. But the two mentioned provided, as far as one can determine so far, the largest contingents.

The migrant leaders Mattheis Müller and Peter Becker demonstrably came from Orzechowo (Orschokowin) (see section 2.4.2.2 Krasnaer aus Orzechowo, document from 1808). According to the previous findings, this place was the northernmost place of origin of Krasnaer Warsaw colonists. It was here that the first group of onward migrants began their journey.

In the spring of 1814 the recruitment and registration of the interested people began. For this purpose the Russian government sent a commission to Poland. It was headed by the Russian state official Krüger. The commission was to make preparations for the recruits' journey to Bessarabia.

Eugen Kossmann, who has done much research on Germans in Poland, gives an example of how the procedure went: „In May (1814) a certain Krüger is said to have …appeared, posing as an advertising commissioner for colonists emigrating to Russia, and writing down all those who wanted to go there…He explained to the peasants…that it was enough if he forwarded their applications to the governor-general, and then they would be sure of Russian entry passports.“

The said Krüger was not only a recruiter, he was also in charge of the transports.

The colonists had to meet at certain assembly points specified by the Russian recruiters. given by the Russian recruiters, e.g. in Lodz and Warsaw. Here they were provided with instructions and travel documents and divided into columns.

It is not directly handed down, but it is quite conceivable that in the Zamość area such an assembly point was also provided for, because 73 German families alone are known to have moved from this region to Russia in 1814, many of them to Krasna.

Albert Mauch, who was the head of the teacher training college in Sarata, says: „In most cases, the German emigrants had already come together in their homeland according to place of origin, kinship, creed and mutual sympathies. This was entirely in accordance with the wishes of the Russian government…,“ because it reduced the potential for conflict.

People set out in groups/departments after electing a leader, the transport or wandering mule, from among themselves. The Wandererschulzen served as guides, signposts, and protectors. For Krasna, the „Wanderschulzen“ Peter Becker and Mathias Müller are mentioned.

One group of the later Krasnaers demonstrably came from the Zamość area (from Sitaniec/Schitanitz), another group from Posen-Wreschen and one from the Plock-Warsaw area. Perhaps the Russians brought them together on the way.

However: larger trains (up to 140 families) used to move accompanied by Russian officials. However, there is no mention of such trains in the case of the Krasna colonists. After all, 133 families of colonists are said to have set out for Krasna. Can we conclude that they did not move in one group, but in at least two or three sections (after all, the settlements in Krasna also took place in three stages-1814, 1815, 1816-)?

At least in all of Krasna's neighboring colonies that were settled in 1814 - 1816, the settlers came in several trains, e.g..

- Tarutino: immigrants did not come in one train, but in several small batches

- Leipzig: they came in three travel groups

- Klöstitz: in several sections

- Borodino: in two groups

- Wittenberg: in several groups led by a Russian official.

The emigrants probably began their arduous journey to Bessarabia in the summer of 1814. They used the overland route. According to Krasna's 1848 parish report, the journey was „partly on their own poor carts, partly on rented wagons. Many also came on foot.“

There were no comfortable and efficient means of transportation available for the long and arduous journey. At that time there were no paved roads and no railroads, much less an automobile.

They had to struggle to cover daily distances of about 20 - 25 km, often camped in the open, far from any village. There were no roads as we had imagined them, the paths were rutted. No navigation system, but simple route descriptions led them to their destination. Today, we probably can't even imagine how strenuous and full of obstacles this journey was.

According to various sources, the itinerary led from Warsaw and other places in Poland to the Russian border in the Volhyn Governorate, on the orders of the Russian government. (It bordered the Polish governorate of Lublin, which was home to many later Krasna residents in the Zamość region). There, people were received and forwarded by Russian authorities.

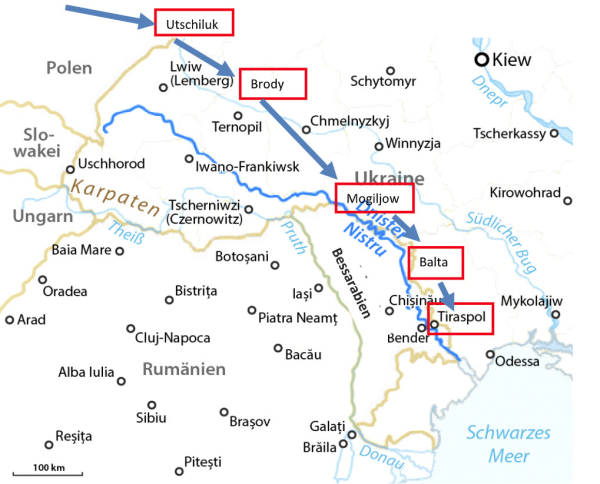

According to the Krasna parish report of 1848, the later Krasna people crossed the border at Uchiluk on the Bug River. This border crossing is also mentioned in the community report of the neighboring colony of Wittenberg. In 1814, the Polish Bug River formed the border between the Duchy of Warsaw and Volhynia, which belonged to Russia. The place is called today Ukrainian Устилуг; Russian Ustilug, Polish Uściług, lies on the eastern side of the Bug and belongs to the Ukrainian oblast Volhynia.

From there, the route continued northeast along the Carpathian Mountains via Podolia to the Dniester River to Tiraspol. The already mentioned Albert Mauch thinks „The grandfathers of the Bessarabian colonists from Poland probably came the way via Brody, Mogilyov on the Dniester, Balta, Tiraspol, Bender.“

According to maps on the Internet, today the shortest footpath via the above places from Sitaniec to Tiraspol is 840-850 km. With a daily mileage of 20 km, it would have taken 42 days to cover the distance without breaks. With breaks, probably just under 2 months is the lower limit. The distance Orzechowo -Tiraspol is even over 1300 km.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Karte_Dnister.png

Maximilian Dörrbecker (Chumwa) -CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)

Under many hardships, sufferings and privations, our emigrants had arrived in Tiraspol in September 1814. The journey ended there first. Here all formalities were completed, the settlement site was instructed and temporary accommodation was organized.